An Elephant in the Archives

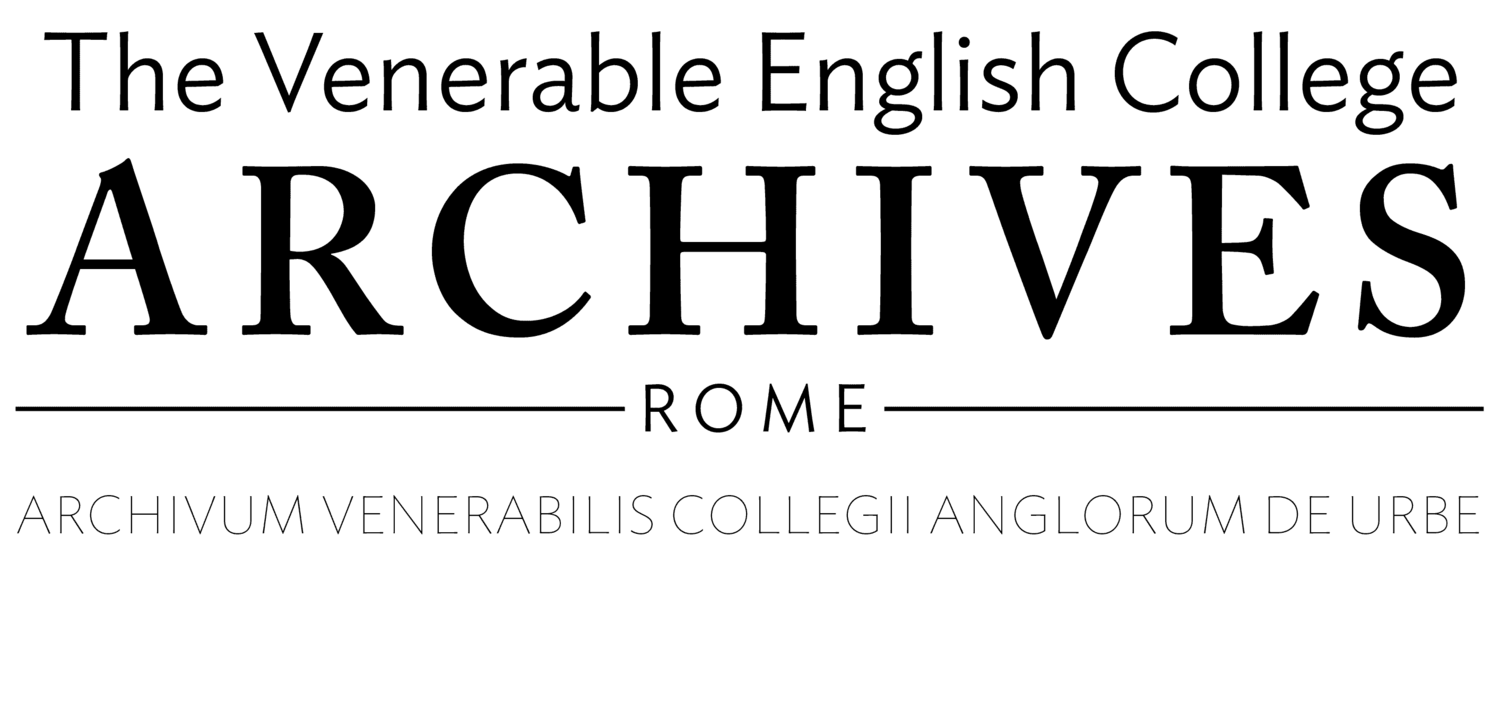

Don Diego performing tricks in Germany in 1629: Wenceslas Hollar

The Tame Elephant WikiCommons — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wenceslas_Hollar_-_The_tame_elephant.jpg

Among the collections in the Archives of the Venerable English College are detailed financial records dating from the sixteenth century onwards. These include accounts of each student’s personal expenditure. We find students paying for scribes and music tutors, purchasing books and having them bound, travelling and alms-giving, acquiring rosary beads and reliquaries, and regularly renewing their wardrobes with gloves and hats; in one case, Thomas Thorold (alias Carwell) (1600–1664) spent eight crowns on a riding coat, umbrella, sword and hat in just one month (AVCAU Liber 309, p 149). They thus provide a unique and often vivid insight into the daily life of early modern Englishmen in Rome.

Recently Alana Mailes, a Harvard PhD student in musicology, has been examining these accounts in search of traces of the College’s musical life in the seventeenth century. But she also uncovered several surprising references to an elephant in the accounts. We soon discovered that in May 1630 an elephant arrived in Rome, whose extraordinary movements have been traced in detail by Louise Rice.[1] The previous elephant seen in Rome had been Leo X’s much-loved pet, Hanno, who died in 1516 and whose remains were discovered under the Cortile del Belvedere in 1962.[2] The thirteen students of the Venerabile who went to see the creature in 1630 were in good company: princes, artists, and intellectuals flocked to see the elephant as he made his way across Europe and the powerful impression this exotic animal made is witnessed in the drawings, sculptures and literary works he inspired.

Born in the Indian subcontinent around 1619, the elephant, known as Don Diego, was sent by ship to Lisbon and displayed at the court of the King of Spain and Portugal. In 1623, during the fraught negotiations for an English-Spanish match between the Spanish Infanta, Maria Anna, and the future Charles I, the elephant was gifted, along with a few camels, to Charles’s father, James I, at the suggestion of the Duke of Buckingham (Rice, 555).

The unusual gift received a mixed response. As the negotiations for the marriage continued to stall, the Venetian ambassador quipped that ‘The King of Spain has sent his Majesty the present of an elephant. I do not know whether it comes as an earnest of the Infanta or instead of her’ (Calendar of State Papers Domestic [CSPD], July 1623). In his masque, Neptune’s Triumph for Albion returned (1623), Ben Jonson mocks the gossip and pomposity of the court with reference to ‘The master of the elephant or the camels’.[3] James had indeed appointed Buckingham’s servant, John Williams, as ‘keeper of the elephant’ and gave strict instructions that the creature ‘be well dressed and fed, but not led out to water, nor allowed to be seen by any, on pain of the ‘uttermost peril’’ (CSPD, 6 July 1623).

It soon became apparent that the royal elephant’s upkeep would be costly, requiring ‘a gallon of wine daily from September to April, when his keepers say he must drink no water’ (CSPD, 24 August 1623). In late May 1625, the elephant is reported to have killed a man; the exact circumstances are unknown, but Gilbert Primrose, who records the death in a letter, describes ‘a grite terrour and scare to the curiositie of the people’.[4] By now Don Diego seems to have outstayed his welcome and soon after Charles’s marriage to Henrietta Maria and accession to the throne, Don Diego passed into private hands and began his tour across Europe.

From 1626 to 1634, the elephant travelled through France, the Low Countries, Germany, Austria, and Italy (Rice, 555). In May 1630, he arrived in Rome and was exhibited in the Palazzo Venezia until mid-June, where thirteen students of the Venerable English College would see the extraordinary animal for the first time in their lives.

The account book records each student paying one giulio for the spectacle, described as ‘for the sight of an elephant’ or, cryptically, ‘for an elephant’. Fr William Rees (alias Owen) and Henry Thimelby (alias Ashby), a convictor or lay boarder at the College who would later marry Gertrude Aston, were the first to visit Don Diego on 8 May. Over the next month trips were made by Thomas Giffard (alias Charles Barker), a convert from Berkshire, Richard Wake, born to English Catholic exiles in Antwerp, and Fr Maurice Keynes, SJ. Valentine Harcourt (alias Lane), and Richard Critchley (alias Christopher Foster), who had entered the College together on 20 October 1629, both went to see the animal in May. On 10 June, two former students of St Omers College, who also entered the VEC in October 1629, Thomas Fazakerley (alias Ashton) of Croxteth Park, Lancashire, and Edward Clark (alias Seaborn or Powell) of Herefordshire made the visit. John Riley (alias Richard Danby), also a former student at St Omers, seems to have gone alone the next day. Just before the elephant left the city, William Critchley (alias Foster), John Lacon (alias Lambert), and George Powell (alias Donwall), all caught a glimpse on 15 June (AVCAU, Liber 309).

Nicolas Poussin, Hannibal traversant les Alpes à dos d'éléphant, c. 1630

WikiCommons — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hannibal_traversant_les_Alpes_%C3%A0_dos_d%27%C3%A9l%C3%A9phant_-_Nicolas_Poussin.jpg

All in their mid-twenties and harking from rural England and Wales, the students must have experienced great excitement at their sight of Don Diego. Their knowledge of elephants is likely to have been minimal. They would undoubtedly have been familiar with Livy’s famous description of Hannibal crossing the alps with elephants in his history of Rome, of which several early modern copies still survive in the College library. They may also have read Pliny the Elder’s Natural History which devotes twelve chapters to the elephant and claims that it is not only the largest animal but ‘the nearest to man in intelligence’ and possesses ‘virtues rare even in man, honesty, wisdom, justice’.[5] Such claims for the superior talents of elephants may have been affirmed by Don Diego’s various tricks: contemporary accounts describe him drinking wine from a glass, smoking tobacco, and delicately peeling oranges with his tusk (Rice, 561).

Sir Kenelm Digby, who visited the English College regularly in the 1640s, and who, as one of the English ambassadors to Spain in 1623 may well have seen Don Diego there, was fascinated by the mysterious abilities of elephants, but he took a sceptical view of such tricks. In his 1644 philosophical Two Treatises, after listing the marvels attributed to elephants, he argues that ‘because the teachers of beastes, have certaine secrets in their art, which standers by do not reach unto’, it would be impossible to judge the abilities of elephants ‘unlesse we had the managing of those creatures, whereby to try them in severall occasions, and to observe what cause produceth every operation they doe’.[6]

For most however, the arrival of the elephant was sensational. Don Diego’s reception at Montreuil-sur-Mer during the summer of 1626 is telling. The elephant’s keeper had banned anyone from seeing him, hoping to reserve the first viewing for the French king; furious, the mayor and leading citizens ‘barricaded his enclosure’ and Don Diego was forced to make his escape by charging away and breaking down part of the city gate (Rice, 563). It seems that the citizens of Montreuil-sur-Mer were not going to give up the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity of seeing one of these fabled creatures without a fight.

The trips of students from the Venerabile to see Don Diego must have been more than a welcome break from studying then; far from home, the students enjoyed an extraordinary encounter with the unknown.

Among Don Diego’s other illustrious visitors were the French painter Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), who made the trip at the suggestion of Cassiano dal Pozzo (1588–1657), secretary to Francesco Barberini (1597–1679, then Cardinal Protector of the Venerable English College. As Louise Rice has recently revealed, Poussin’s Hannibal Crossing the Alps is in fact primarily a zoological portrait of Don Diego embellished with some historical narrative details (Rice, 550). It is also very likely that Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) saw Don Diego in Rome and that he was influenced by the spectacle when preparing plans for an elephant obelisk for Cardinal Barberini in the 1630s. This project was never realised, but the later Elephant and Obelisk placed in front of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva in 1667 may well have been informed by Don Diego’s visit (Rice, 576).

Bernini’s Elephant, Santa Maria sopra Minerva

(WikiCommons: Alvesgaspar [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)])

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elephant_Bernini_September_2015-1.jpg

The thirteen members of the Venerable English College who saw the elephant in Rome are just a small part of the extraordinary story of Don Diego. Their visit illustrates the wide variety of people who must have seen the creature, though what effect it had on each of them can only be imagined.

This surprising discovery is just one more example of the sheer range and detail of the archival collections at the Venerable English College and further evidence of the rich history of the experiences of the English and Welsh Catholic community at home and abroad.

[1] Louise Rice, ‘Poussin’s Elephant’ Renaissance Quarterly 70.2 (2017): 548–593.

[2] Silvio. Bedini, The Pope’s Elephant: An Elephant’s Journey from Deep in India to the Heart of Rome (Manchester: Carcanet, 1997).

[3] Ben Jonson, ‘Neptune’s Triumph for the Return of Albion’ (1624), The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson, line 176.

[4] Louise Rice, Addenda to ‘Poussin's Elephant’ (10 April 2018), <https://www.academia.edu/36391622/Addenda_to_Poussins_Elephant_>

[5] Pliny, the Elder, Natural History, Loeb Classical Library, ed. A. C. Andrews et al (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2014), Book 8, Chapter 1, p 3.

[6] Kenelm Digby, Two treatises in the one of which the nature of bodies, in the other, the nature of mans soule is looked into in way of discovery of the immortality of reasonable soules (Paris: Printed by Gilles Blaizot, 1644), 321.

![Bernini’s Elephant, Santa Maria sopra Minerva(WikiCommons: Alvesgaspar [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)])https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elephant_Bernini_September_2015-1.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bba9a547a1fbd2c0613ea13/1561018416635-5JI7WVUL2NMPV4OCE6F3/Screen+Shot+2019-06-20+at+09.59.43.png)